The Body Snatcher was one of the later RKO horror B-films produced by Val Lewton and was a major commercial success for the studio. It was shot in 1944 and released in 1945. It was the first of the three Lewton films to star Boris Karloff (actually Isle of the Dead should have been the first but production was temporarily halted and it was completed after The Body Snatcher).

It was based on Robert Louis Stevenson’s story of the same name which was based in turn on the infamous West Port Murders (for which Burke and Hare were believed responsible).

The story takes place in Edinburgh in 1831. Dr MacFarlane (Henry Daniell) is not only a very prominent doctor but also a renowned teacher at Edinburgh’s famous medical school. Like his predecessor Dr Knox (who was involved in the Burke and Hare case) Dr MacFarlane has one major problem - the immense difficulty of obtaining a sufficient supply of cadavers for his students. His main source of supply is a cabman named Gray (Boris Karloff). Gray has a knack for supplying bodies when needed. The bodies in fact are obtained from grave-robbing.

In the West Port Murders case it was alleged that Burke and Hare not only robbed graves but also hastened the deaths of the unfortunates who provided the cadavers. We have our suspicions right from the start that Gray may well be doing the same thing. Dr MacFarlane certainly has very strong suspicions but he dare not voice them. For one thing he himself could well be implicated in any investigation. Secondly, he wants those cadavers for his students. And finally, it is clear that Gray has some sort of hold over him.

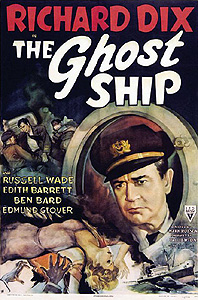

MacFarlane’s new assistant, Donald Fettes (Russell Wade), wants to give up studying medicine entirely when he discovers Gray’s activities. He is persuaded not to do so by MacFarlane. MacFarlane argues that the benefits for society (more and better trained doctors) outweighs the evils of grave-robbing and possible murder. To what extent both MacFarlane and Fettes have really convinced themselves of this we are not really sure but the internal moral dilemmas faced by both men provide much of the movie’s impetus.

There’s a sub-plot involving a little girl who needs an operation in order to be able to walk again, and Dr MacFarlane is the only man capable of performing it. This sub-plot could have been merely an excuse to indulge in some cheap sentimentality but it’s used quite cleverly in order to give us a much greater insight into Dr MacFarlane’s very troubled mind.

Lewton was more interested in movies that explored interesting psychological states rather than just horror pictures as such. The basis of his success at RKO was his ability to produce movies that combined both psychology and horror. In The Body Snatcher the real core of the story is the complex and unhealthy relationship between Dr MacFarlane and Gray and the resulting psychological power struggles between the two men.

Like all the Lewton RKO productions this movie is more character than plot-driven. This means that the actors are required to do some real acting. That proves to be no problem. Karloff was delighted with his role, realising instantly that it was going to give him the opportunity to really show his acting chops. He delivers a superb performance. For Henry Daniell it also offered one of his best roles and he made the most of it.

Karloff and Daniell dominate the movie entirely. Russell Wade is more than adequate but inevitably he is hopelessly overshadowed. Bela Lugosi is relegated to a minor role which he carries off reasonably well (this was to be the last film in which Karloff and Lugosi appeared together).

For this film it was going to be necessary to evoke the feel of early 19th century Edinburgh. Medieval Paris might not sound like an ideal match but Lewton realised that standing sets built for The Hunchback of Notre Dame would in fact be quite suitable for this purpose.

The original script for The Body Snatcher was written by Philip MacDonald but it was Lewton himself who was responsible for the final shooting script (although as always he used a pseudonym for his writing credit).

Lewton was one of that small handful of producers who not only wanted to make a genuine creative contribution to their movies but also had the talent actually to do so. Perhaps even more importantly he seemed to have the ability to do this without treading on the toes of either his directors or his writers. One of the most effective scenes in the picture, in which a young street singer is seen walking away from the camera down a street leading into a kind of tunnel, was (according to Robert Wise) one of Lewton’s ideas.

Lewton had given Robert Wise his first opportunity as a director when he assigned him to complete The Curse of The Cat People. The Body Snatcher was his third film for Lewton. On the whole Wise does a fine job. He lacks the true visual genius of a Jacques Tourneur but The Body Snatcher is still an impressive-looking film.

The DVD supposedly includes an audio commentary track by director Robert Wise. What it actually is is a lengthy interview with Wise, but it’s still quite interesting even if he doesn’t have a huge amount to say specifically about The Body Snatcher.

The transfer featured on the DVD is superb.

The Body Snatcher is not quite in the top rank of the Lewton horror films but it’s a good movie nonetheless, offering the usual Lewton blend of intelligent thoughtful horror (particularly impressive in this case with subject material that would tempt most film-makers to take a much more sensationalistic and exploitative approach). Highly recommended.